- Savage Blog

- Who was Aldo Leopold?

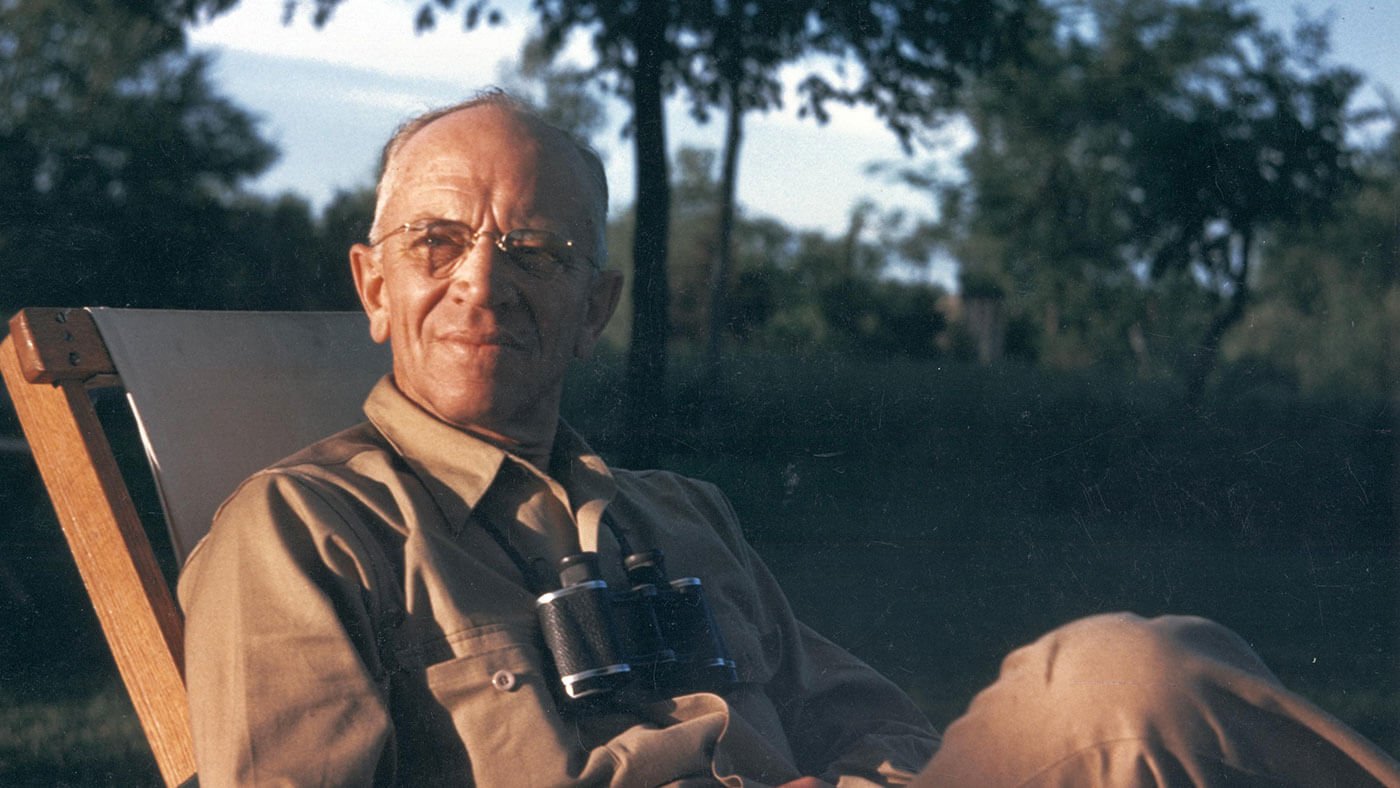

Who was Aldo Leopold?

Aldo Leopold, known as the Father of Wildlife Ecology and the US Wilderness System, is one of the most influential thinkers in North American conservation history. Living 61 years, from 1887 to 1948, Leopold’s life and career in conservation spanned the initial emergence of the modern conservation movement. Leopold played a significant role in the development of modern conservation by being an active part of the movement, while also being a leading philosopher about how the movement evolved over time.

__

“There are two things that interest me: the relation of people to each other, and the relation of people to land.” – Aldo Leopold

__

Over the four decades of his career and continuing to today, Leopold’s tremendous influence on conservation is a result of his observations, ideas and actions, but also because he was an incredibly skillful communicator. He used those skills to promote his views about conservation and guide the direction of the conservation movement.

Born and raised in Burlington Iowa, Leopold earned a degree from the Yale School of Forestry and in 1909 and began a career with the US Forest Service. He spent the next 15 years in Arizona and New Mexico where he was instrumental in the designating the Gila National Forest Wilderness Area, the first wilderness area in the nation. In 1924 he transferred to the US Forest Service Forest Lab in Madison, Wisconsin which would be his home the rest of his life.

__

“Wilderness is a resource which can shrink but not grow… creation of new wilderness in the full sense of the word is impossible.” – Aldo Leopold

__

Leopold’s Ideas on and Work in Wildlife Conservation

Leopold was a hunter throughout his life. After arriving in Madison, the rest of his career and work centered around wildlife ecology and management, improving native landscapes and habitat for game species and all wildlife.

After leaving the US Forest Service in 1928 Leopold became a pioneer in the emerging field of game and wildlife management. Game and wildlife species in the Midwest were in trouble and Leopold began to work to find out why. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute (SAAMI), of which the Savage Arms Company was a member, funded Leopold to complete a 3 year study and series of game surveys across the upper Midwest. In 1931, A Report on a Game Survey of the North Central States was published. What Leopold learned, concluded, and proposed from conducting the survey would change the direction of wildlife conservation.

Wildlife Conservation in the first quarter of the 20th century was based, because of the experiences of the extinction of the passenger pigeon and the near extinction of the American buffalo, on protection of species. But even with a focus on protection, games species like wild turkeys, whitetail deer, raccoons and other wildlife species were not thriving, and Leopold realized that the recurring problem throughout the study area was not the over exploitation of the game species, but rather the poor condition of the habitat, much of it because of the demands put on the land by the farming and forestry practices of the day. At the same time Leopold was learning about the emerging science of ecology, the relationship between living things and their habitat. He tied ecology to conservation and concluded that active management of habitat and wildlife would improve both.

__

“The central thesis of game management is this, game can be restored by the creative use of the same tools which have destroyed it—axe, plow, cow, fire, and gun.” – Aldo Leopold

__

In 1933 Leopold joined the faculty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and published the textbook Game Management in which he describes all the things he had learned in his career, linking and tying it all together with the principles of ecology. His text taught that the way forward for all wildlife conservation, not just game species, but all species, is science-based management based on ecological principles. The discipline of Wildlife Ecology as we know it today was born.

While at the University of Wisconsin, Leopold not only taught these management principles, but he was also able to help implement them. During the 1930’s, the newly created Soil Conservation Service (now Natural Resource Conservation Service) planned and implemented soil and water conservation practices throughout the Midwest and Leopold worked with NRCS to include habitat improvement and show how wildlife could also benefit from these soil and water conservation practices.

__

“Conservation will ultimately boil down to rewarding the private landowner who conserves the public interest.” – Aldo Leopold

__

Land and forest management practices aimed at sustainability that benefit the entire ecosystem and the members of it, on both private and public land, can be traced back to this era. Today’s game management professionals and principles are like wise anchored in the teachings and era of Leopold.

The Riley Game Cooperative

In 1931 Leopold stumbled upon the small Wisconsin town of Riley, southwest of Madison, while on an expedition searching for permission on a new place to hunt. There he met a local farmer named Reuben Paulsen. After lamenting the lack of game with Paulsen, who was troubled by hunter trespass on his land, the need for game and land management in the community became apparent. Leopold saw the opportunity to put his wildlife ecology ideas into practice. With the help of Reuben, other Riley farmers, and friends from the Madison area, the Riley Game Cooperative was formed. This cooperative served as a way to share in the work of habitat improvement, socialize and share in the hunting rewards of the work. Leopold also used Riley as an outdoor classroom and his students helped plan, implement, and document the work, game harvests and progress on RGC properties.

__

“I needed a place as to try management as a means of building up something to hunt. We concluded that a group of farmers working with a group of town sportsmen, offered the best defense against trespass and also the best chance for building up game. Thus Riley was born.” – Aldo Leopold

__

Examples of the work and cooperation of the Riley Game Cooperative:

- Farmers supplied the land and feed.

- Members supplied money for eggs or pheasants that the farmers family raised.

- Members supplied signs to mark the boundaries of the cooperative.

- Both groups provided labor to plant trees and brush for cover and to build brush shelters

- RGC became an Outdoor classroom and a community of farmers and town sportsmen.

Bob & Janet Silbernagel “Tracking Aldo Leopold through Riley’s Farmland, Remembering the Riley Game Cooperative”

A Sand County Almanac and Leopold’s Legacy

Leopold’s best-known work, A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There is the culmination of his life’s work and experience as well as his fully developed conservation philosophy. The book is timeless and is geared towards a general audience. It is a series of essays connecting the reader to the land, the plants and animals that occupy it while describing it all in a most engaging and wondrous way. The almanac section of the book is written about the relationship Leopold and his family have with a worn-out piece of land near Baraboo, Wisconsin that they lovingly work to restore, while observing the passings of the seasons.

In the middle of the book, Leopold describes landscapes he has visited and known around the country and how humans have used, and in some cases, abused them. Leopold discusses the different ways people use the land and the reader sees his philosophy of conservation take shape.

__

“A land ethic, then, reflects the existence of an ecological conscience, and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of the land. Health is the capacity of the land for self-renewal. Conservation is our effort to understand and preserve this capacity.” – Aldo Leopold

__

The end of the book, The Land Ethic, is where Leopold clearly states his ideas and philosophy about people living with the land and urges the reader to see the natural world as something we are part, not master, of: “when we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” Now translated into 14 languages, A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There is required reading for conservation students and is largely regarded as providing the moral compass for the modern environmental movement.

Gratitude to:

- Stan Temple for his time, stories and insights about Leopold and Riley. Stan is the Beers-Bascom Professor Emeritus in Conservation in the Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology and former Chairman of the Conservation Biology and Sustainable Development Program in the Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at UW–Madison. For 32 years he held the academic position once occupied by Aldo Leopold. He is currently a Senior Fellow with the Aldo Leopold Foundation.

- Janet Silbernagel for her time, stories and history of the Riley area, the Riley Game Cooperative and her thoughts on cooperative conservation strategies. Janet is Professor Emeritus, Planning and Landscape Architecture at UW-Madison, where she specialized in regional conservation strategies and landscape ecology; building forest conservation scenarios. Janet grew up near Riley and her family property was once part of the Riley Game Cooperative.

- The Aldo Leopold Foundation for information about Leopold and Riley, Leopold archives and photos and access to the Shack and the Leopold farm for inspiration and filming.